Separation of Powers: Doctrine, Case Laws & Critical Analysis

1. The Theoretical Foundation

The doctrine was famously articulated by the French jurist Montesquieu in his 18th-century work, The Spirit of the Laws. He argued that "constant experience shows us that every man invested with power is apt to abuse it."

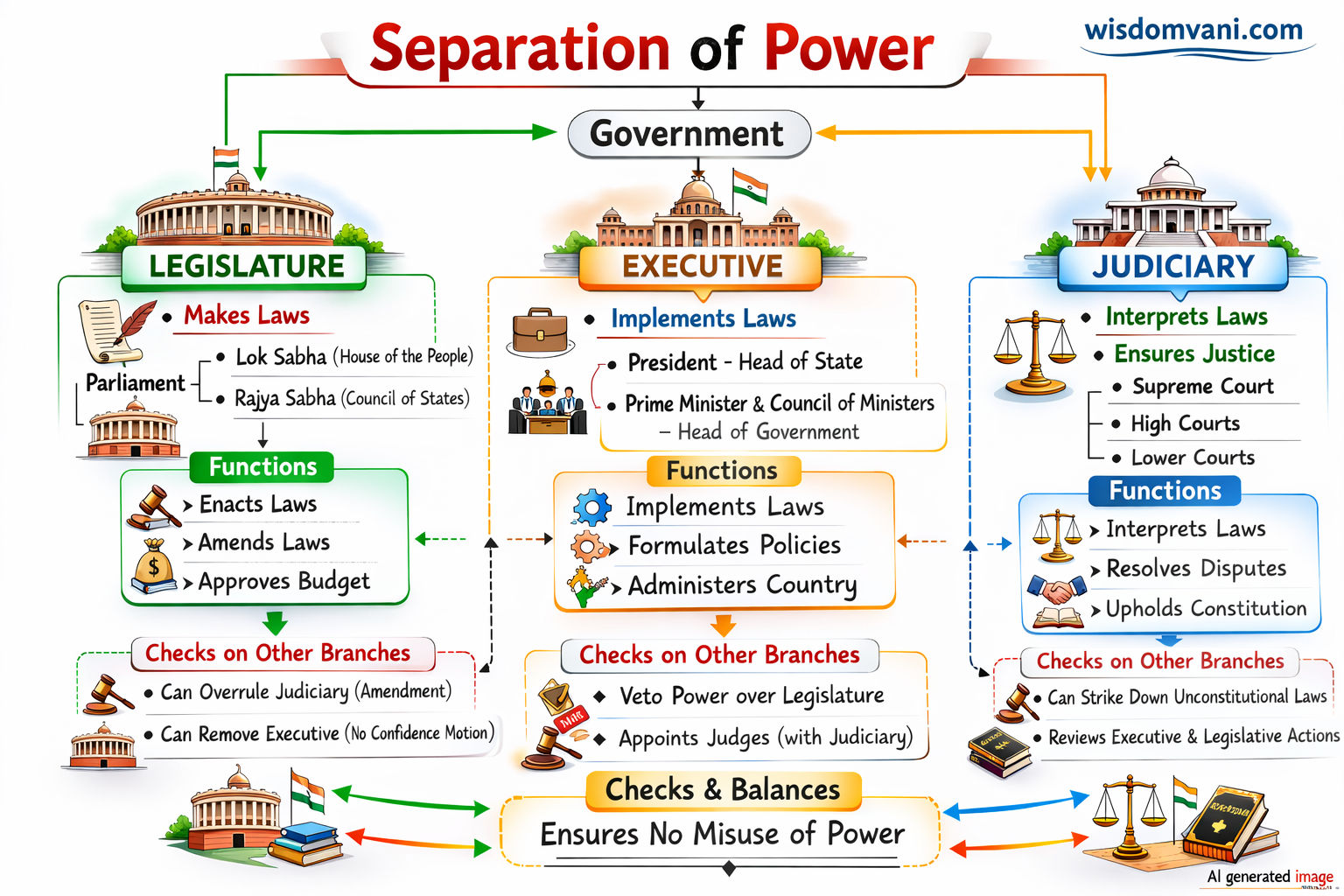

To prevent this, he proposed a tripartite system:

The Legislature: Makes laws.

The Executive: Implements and enforces laws.

The Judiciary: Interprets laws and adjudicates disputes.

In a strict sense, this doctrine implies that no person should be a member of more than one organ, and no organ should interfere with the internal workings of another.

2. The Indian Constitutional Framework

Unlike the United States, where the separation is relatively rigid, India follows a Parliamentary form of government. This creates a "cordial overlap" rather than a "water-tight" separation.

Executive & Legislature: In India, the Executive (the Prime Minister and Cabinet) is physically part of the Legislature (Parliament). They are accountable to it and must resign if they lose the confidence of the House.

Judiciary: The Indian Judiciary is designed to be more independent. Article 50 of the Constitution (a Directive Principle) specifically mandates the state to separate the judiciary from the executive in public services.

3. Landmark Case Laws: The Judicial Perspective

The Indian Judiciary has used its power of interpretation to define how this doctrine applies to our unique democracy.

A. Rai Sahib Ram Jawaya Kapur v. State of Punjab (1955)

This is the leading case establishing that India does not follow a rigid separation of powers. The Supreme Court observed that while the Constitution does not recognize the doctrine in its absolute form, the functions of the three organs are sufficiently differentiated.

The Rule: The Executive can exercise certain legislative powers (like making rules) as long as it does not violate the law made by Parliament.

B. Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala (1973)

This landmark ruling declared that the Separation of Powers is part of the "Basic Structure" of the Constitution.

The Impact: This means that even with a 100% majority, Parliament cannot pass a Constitutional Amendment that destroys the balance between the three organs or takes away the independence of the Judiciary.

C. Indira Gandhi v. Raj Narain (1975)

In this case, the 39th Amendment was challenged because it attempted to place the Prime Minister’s election dispute outside the jurisdiction of the courts.

The Ruling: The Court struck down the amendment, holding that "adjudication" is a purely judicial function. Parliament cannot perform a "judicial act" by deciding a specific legal dispute through legislation.

D. I.R. Coelho v. State of Tamil Nadu (2007)

The Court reaffirmed that the separation of powers is essential to the Rule of Law. It held that any law that violates the fundamental rights of citizens is subject to Judicial Review, which is the ultimate "check" the Judiciary holds over the Legislature.

4. Critical Examination

While the doctrine aims for a perfect division of power, the practical reality in a modern welfare state is much more complex.

I. The Overlap of Functions

In India, the lines are often blurred:

Legislative Powers of the Executive: The President can issue Ordinances (Article 123) when Parliament is not in session, which have the same effect as a law.

Judicial Powers of the Executive: Administrative Tribunals (like the Income Tax Tribunal) are part of the Executive branch but perform judicial tasks.

Legislative Powers of the Judiciary: Under Article 142, the Supreme Court can pass orders to ensure "complete justice." In cases like Vishaka v. State of Rajasthan, the Court actually laid down guidelines that functioned as law until Parliament enacted a statute.

II. The Challenge of "Judicial Activism"

A major point of critique is the rise of Judicial Activism. When the Legislature fails to act or the Executive is inefficient, the Courts often step in to fill the vacuum. While this protects citizens, critics argue it is "Judicial Overreach"—where judges begin to make policy decisions (like managing traffic or urban planning) for which they lack the expertise or democratic mandate.

III. Administrative Necessity

In a complex society, Parliament cannot foresee every detail. Thus, they pass "skeleton legislation" and delegate the power to make detailed rules to the Executive (Delegated Legislation). This technically violates the strict doctrine but is a practical necessity for efficient governance.

5. Conclusion

The Doctrine of Separation of Powers in India is not a formula for isolation, but a formula for accountability. We do not have "Separation of Powers" in the literal sense; we have a Functional Overlap moderated by Checks and Balances.

The Legislature checks the Executive through the "No-Confidence Motion." The Executive checks the Judiciary through the appointment process. The Judiciary checks both through "Judicial Review." This delicate balance ensures that the "Spirit of the Laws" is maintained, even if the boundaries are occasionally fluid.

Comments 0